TUMWATER STRIKES BACK

I have an old neighbor with a lot of junk piled up in his yard. His name is Tumwater. I love this guy. We’ve been friends for over 30 years. I may not understand him as well as some of you, but I’m writing to share what he told me as I trespassed through his 100-acre brewery ghost town.

But first, I need to tell you: the junk is not his fault. There are big, big forces at play, forces that have been gathering strength for the last 65,719 days — that’s the number of days since the first American settlers arrived here. (But who’s counting? Apparently, me.)

ACT I

The story of this deserted brewery starts the first week of November, 1845. The Bush-Simmons Party arrives. The Steh-chass offer a longhouse at the base of the falls. This party of American pioneers isn’t just the first to settle in the South Sound. They’re the first ones to settle in the state.

That foothold north of the Columbia helped end decades of border haggling with England. A growing population of settlers, centered around Tumwater and the later settlement of Olympia (founded 1850), leads to the movement for separating from Oregon. This culminates in the establishment of the Washington Territory in 1853.

Let’s pause here. Re-read the last paragraph so it sinks in. Please, appreciate the significance of this: Tumwater is where this state — the 42nd star on the flag — truly begins. I think this gets downplayed, and it shouldn’t. It gets downplayed for a reason: a series of demoralizing historic vectors.

A historic vector is a force of change, like a new technology: a river, a paved road, a train, a highway, a plane. Tumwater had a dozen others. Each vector did the same: things bloomed, became outdated, and were abandoned.

A couple articles back, I planted the seed for this one when I wrote, “In 1952, Tumwater officials made a shocking decision: they voted to abandon their downtown core.” The oldest U.S. city in Washington was deliberately surrendered, demolished and buried under millions of tons of asphalt and concrete.

I understand that even before it was buried, the site of downtown Tumwater had stopped being ideal. People didn’t need river access, there wasn’t a train station, and the 5th Avenue dam eliminated the Tumwater maritime port. My beef is that they didn’t salvage the relics and use them to rebuild a new downtown. Instead, Tumwater moved south. Sure, good things came from that. Tumwater’s population skyrocketed, but its soul never recovered.

The absence of a downtown was a loss, but a bigger one, the biggest one of all, came at 5 p.m. on June 20, 2003.

With a final whistle, the brewery closed for good. An unprecedented silence settled over the machines. Time stopped.

ACT II

Today, more than two decades later, not just Tumwater, but the whole county is still reeling. Brewery despair lingers, evident in the failure to make something new from the rusting hulk of the old brewery complex.

Don’t send me any more links... I get it. There are all sorts of fancy supplemental reasons why the brewery closed and remains vacant. But, not coming to terms with loss is the biggest reason. It’s why there hasn’t been public will (or public funding) to make something new here.

And, in case the symbolism is lost, we’re not talking about an old factory on the outskirts. This gigantic fortress, literally and figuratively, sits in the historic heart of everything.

The City of Tumwater and The Tumwater-Olympia Foundation are trying to push back, but the forces working against them are far more powerful. This was on display last month at Falls Fest, a family-friendly fair that celebrates “the historical significance of the area.”

I had a good time. I played croquet and cornhole. They had a lot of white folding chairs set in neat rows. I never saw anyone sitting in them. There was an old-timey bluegrass band. And the whole thing was happening in the shadows of the towering vandalized, overgrown million-square-foot relic that has sat unoccupied for 1,164 weeks. (Ugh. I can’t stop counting.)

I kept lapsing into fits of depression, shouting to Daniel, who was filming me for his Instagram (H.E.A.L. Olympia), “How do we turn such a blind eye to so much lost potential? Why do we treat the birthplace of Washington State with such disrespect? How have we not found the will to do something better than this?”

Facing the loss of the brewery is part one. For the other part, I think we could learn something from 1896. At the same site as that longhouse where the Simmons-Bush party spent their first winter, Leopold Schmidt purchased the old Biles & Carter Tannery and converted it into a brewery. Over the next hundred years, he and his friends met the winds of change with creativity.

During Prohibition, the brewery would have passed away if it weren’t for alternatives that included the production of unfermented fruit juice. They also sold purple cakes of dehydrated wine and tan ones made from shredded hops. These could be mixed with a bottle of mouthwash to create a disgusting, yet dizzying aperitif.

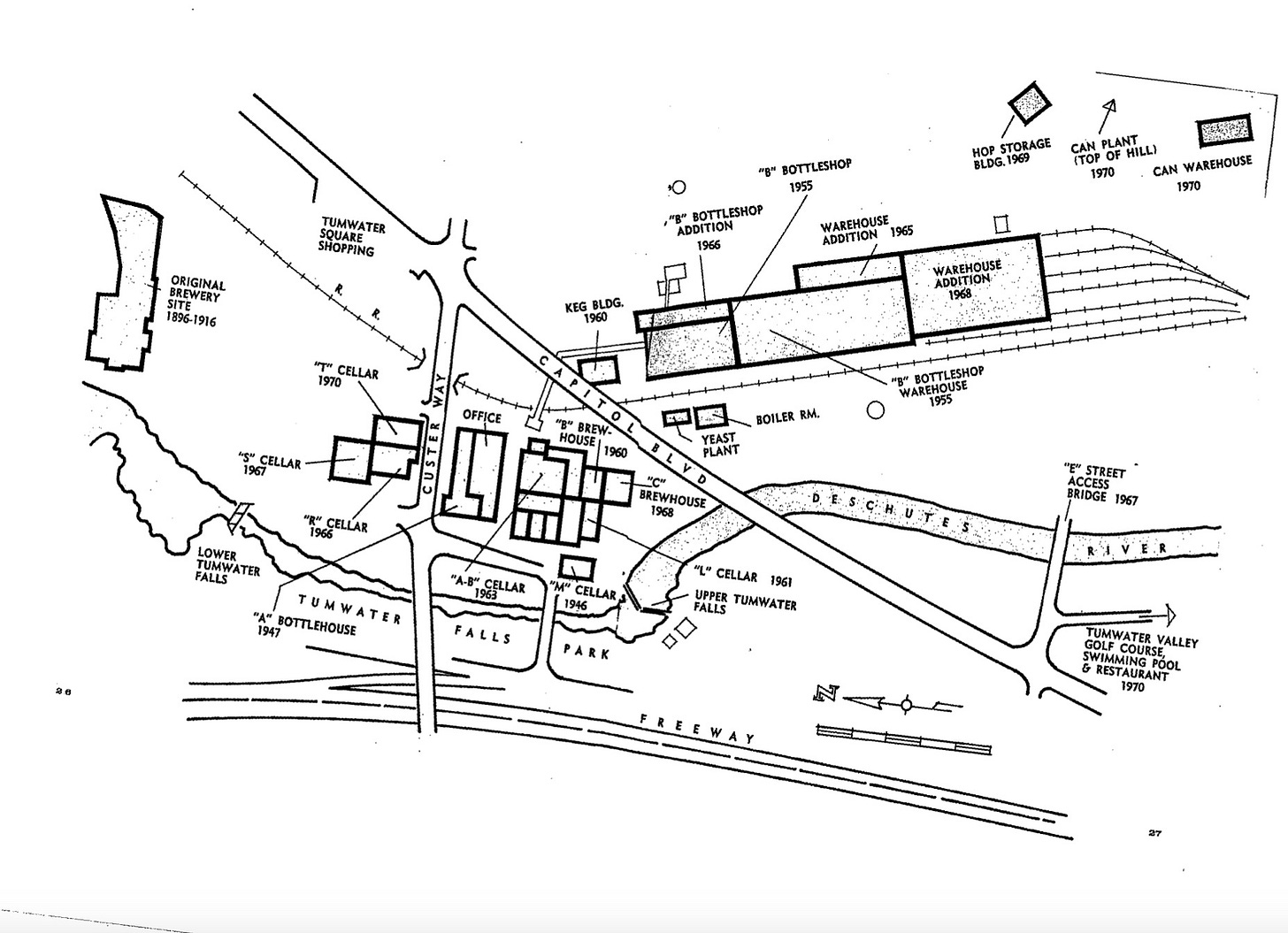

After Prohibition, the brewery hit the ground running with a catchy ditty about the purity of the water. By 1955, Olympia Beer was one of the most successful beer brands in the world. The operation scrambled to keep up with demand, sprinting through the rest of the century in a persistent state of facility expansion along the Deschutes River. For seven solid decades, beer was the chief industry of the city. New technologies and high-speed conveyor belts allowed barrels to roll out by the millions.

Then everything stopped. A year went by. The shuttered property was purchased by the Nevada-based All-American Bottled Water Corporation with intentions to re-open the facility as an all-American bottled water operation. It seemed like such a perfectly poetic new purpose. “It’s the water,” would become, “It’s water.”

But the project never got off the ground. It would be wrong to only blame the City of Olympia for that failed project, but seizing the brewery’s water rights through the use of eminent domain law not only raised ethics questions, it closed the door on a future bottling operation.

Olympia added drama to this process by starting it without consulting Lacey or Tumwater. Olympia soon yielded to their wrath and worked out an arrangement where they’d share the seized water. They paid $4.5 million to All-American as “just compensation.”

ACT III

Water is not just a cool last name. It’s also Olympia’s greatest cultural legacy and its greatest natural resource. A freshwater subterranean ocean sits under the entire city. These are the Olympia aquifers. Many are connected to naturally occurring artesian springs. Five years ago, the Tumwater fire department used 1.5 million gallons of it to douse the brewery’s burning administration building. The symbolism was staggering.

After All-American went even more bankrupt, the bank sold the foreclosed property to Capital Salvage (who presumably ripped out as much scrap metal as they could wrestle from the bones of the assorted behemoths). In 2015, Chandu Patel purchased the gutted property from Capital Salvage for $4 million. According to his website, “Chandu is a visionary beacon, a socio-political powerhouse, hotel tycoon and has made millions in the business.” Cool.

The ground under the derelict brewery is riddled with toxic waste. Apparently, making beer requires Aroclor, Clophen, Fenclor, Askarel, and Inerteen, not to mention a lot of heavy metals. When a vandalized transformer led to about 600 gallons of PCB-laced oil spilling into the Deschutes River, scuba crews performed underwater cleanups for two years.

In 2023, the city of Tumwater received a $500,000 award from the EPA. That money was used to cover some of the costs associated with a preliminary assessment of contaminants. A “Phase 1” of the historic records of pollution was completed. This year, they began the process of boring soil samples. These will presumably be studied for a while before concluding that a new study needs to be funded.

We’ve tried denial, abandonment, grants, committees, seizures, condemnations. It’s time to try something old school. The water, beer and spirit of the Olympia Brewery haunts this vacant compound. Walking around it, it’s not hard to channel the ghost of the ingenious Leopold Schmidt.

You can’t resurrect what you refuse to mourn.

CONCLUSION

Enough realism. Let’s dream.

A new city can rise between Olympia and Tumwater from the ruins of this wasteland. It will be called Happy Land, a theme park honoring the first settlers and the brewery that once defined a town. It will be bigger than Colonial Williamsburg. We’ll convert the factories into retro industrial loft apartments with stubby glass water slides and polished steel escalators.

We’ll take back the water rights. We won’t just get beer production humming again, we’ll brew craft beer, draft beer, ginger beer and root beer, contact lens solution, antifreeze, biodiesel, nut milk, and just about every other liquid you can name.

Everyone will have a job. Smiling mustaches with big biceps will juggle giant blue wrenches. Pink skirts on roller skates will deliver cheeseburgers. Our flag will be chrome, turquoise and neon. Rock and roll will never die — it will hydrate. And like cakes of dried wine, we will all float into a new kind of prosperity.

Rise up, Tumwater.

Take back what’s yours.

It’s time.

It’s now.

It’s the water.

I am down witcha! Let's get Happy Land on the ballot!

Wonderful!